Mapping the Jewish merchant community of Amsterdam

/Renate Smit, History RMA student, shares the finding of her exploratory project by digitally investigating Jewish merchants’ spatial use patterns within the city through the name registers (Koopmansboekjes) of Amsterdam at the turn of the 18th century.

A view from Markenbrug towards Valkenburgerstraat. Drawing by G.P. Westenberg (ca. 1810). source: Amsterdam City Archives

Eighteenth century Amsterdam was home to a lot of different people, who lived in various parts of the city. This included a relatively large Jewish community. The Jewish community had begun to form in the sixteenth century and continued to grow in the centuries that followed. Most Jews had fled their countries because of religious persecution and sought refuge in Amsterdam because of its relatively tolerant religious climate and booming economy. Most Jewish people who came to Amsterdam settled in the eastern part of the city together with other migrants and local residents, although they were not forced to do. It all started when the first Jews came to the city and settled on the island Vlooienburg (fig.1). When the most part of the industry on the islands Rapenburg, Marken and Uilenburg moved to another part of town mid-seventeenth century, Jewish people started to settle there as well. The clustering of Jewish people, their language and cultural practices attracted even more Jews to the islands, which came to be called the Jodenbuurt. The Jodenbuurt contained important places for the Jewish community, including synagogues, schools, kosher shops, burial places, ritual baths and butchers. Another aspect that kept the community together socially and spatially was the fact that the elite of the Jewish community was given the right to rule their own community.[1]

Figure 1: Map which shows the core of the Jodenbuurt (the black line) and the gray zones surrounding it (the green line), 18th century, projected onto Buurtatlas Loman from 1876.

In my research, I have studied a part of the Jewish community by looking at the Naamregisters van alle de kooplieden (…) der stad Amsterdam (fig.2).[2] These name registers were published between 1766 and 1838 and contain the names of merchants who lived in Amsterdam, their addresses and what they traded in (fig.3). During my research, I have explored the potential of the name registers in light of the digital tools available for visualizing large sets of historical data and changes in spatial dimensions. As a case study I decided to focus on the data available for Amsterdam’s Jewish merchant community to find out whether there occurred any changes in the community between 1796 and 1800 in terms of trade and location. The results were visualized with Palladio, an online program which turns large amounts of data into maps, graphs, tables and galleries.

Figure 2: Naamregister van alle de kooplieden (…) der stad Amsterdam, Amsterdam 1796, Stadsarchief Amsterdam.

I have chosen to focus on the registers from 1796 and 1800, because 1796 marked a great change for the Jewish people of the Dutch republic. In 1796, they were granted full political rights and were from then on full citizens of the Republic. Henceforth, they could settle everywhere, practice any profession and participate in politics. Before this, Jewish people were unable to become full citizens and were, among other things, excluded from crafts that were regulated by guilds and from holding political positions. The goal of the research was to find out whether the granting of rights resulted in short time changes in the places where Jewish merchants lived and the products they traded in. In order to find this out, the data was visualized in maps (the addresses) and a graph (the products). Visualizing spatial) data can help put historical information in its geographic context, look at it from different scales and map its spatial patterns.

Figure 3: Beginning of the Jewish section of the Naamregister van alle de kooplieden (…) der stad Amsterdam, Amsterdam 1796, Stadsarchief Amsterdam.

In order to use the data from the 1796 and 1800 register, we collaborated with CREATE to gather machine-encoded text per page through Optical Character Recognition technology. After cleaning and structuring the data from the name registers, I linked the different addresses to coordinates and arranged the different products that merchants traded in in different product categories. From the registers, it is unclear whether the addresses that are mentioned for Jewish merchants were their homes, their places of work or both. I clustered the different Jewish merchants per street in order to see which streets were densely used by them (fig.4). Next to that, it is difficult to determine where Jewish merchants lived exactly because their house numbers are not mentioned. Although house numbers were implemented in 1800, Jewish merchants’ addresses appear without them in the 1800 register. In contrast, most non-Jewish merchants appear with a house number in 1800. From my research, it is unclear why this is the case.

In my research, I have decided to focus on the merchants that appeared in the 1796 register as well as the 1800 register, because it is cumbersome to find all Jewish merchants in the name registers after 1796. This has to do with the fact that the name registers contained a separate Jewish section until 1796 (fig.3). After that, the Jewish merchants were merged with the merchants from the non-Jewish section. This means that there is no indication of which merchants were Jewish after 1796. To find all Jewish merchants in registers after 1796 is time-consuming, because all names in the registers have to be compared to other types of registers which contain members of the Jewish community of Amsterdam.

Figure 4: Map which shows the streets that Jewish merchants lived on in 1796 and the coordinates that have been chosen to represent them, projected onto Buurtatlas Loman from 1876.

The map shown below is one of the results of my research (fig.5). It shows the clustering of 124 Jewish merchants per street in 1796. The data is projected onto a historical map from 1876, the Buurtatlas Loman.[3] The size of the dots represent the amount of merchants that lived on the different streets. The greater the size, the more people lived on the streets. Not surprisingly, most Jewish merchants lived in and around the Jodenbuurt. But at a closer look, what stands out is that the majority lived on the more well-to-do streets and canals. There are relatively large clusters on the Jodenbreestraat (15), Zwanenburgerstraat (16), Nieuwe Herengracht (26) and Nieuwe Keizersgracht (22). The Jodenbreestraat and Zwanenburgerstraat housed a lot of middle-class citizens and the grand canals were home to the wealthy. In contrast, there were no merchants who lived on Uilenburg, one of the poorest islands of the Jodenbuurt and only ten lived on Rapenburg, another extremely poor part of the community. The reason for this can be that most Jewish merchants made a reasonable to good living, that there were poor merchants who lived on relatively well-to-do streets or that only the more well-off merchants are included in the register.[4]

Figure 5: Map which shows on what streets Jewish merchants lived, 1796, projected onto Buurtatlas Loman from 1876.

Figure 6: Map which shows where Jewish merchants (who also appeared in the 1796 register) lived, 1800, projected onto Buurtatlas Loman from 1876.

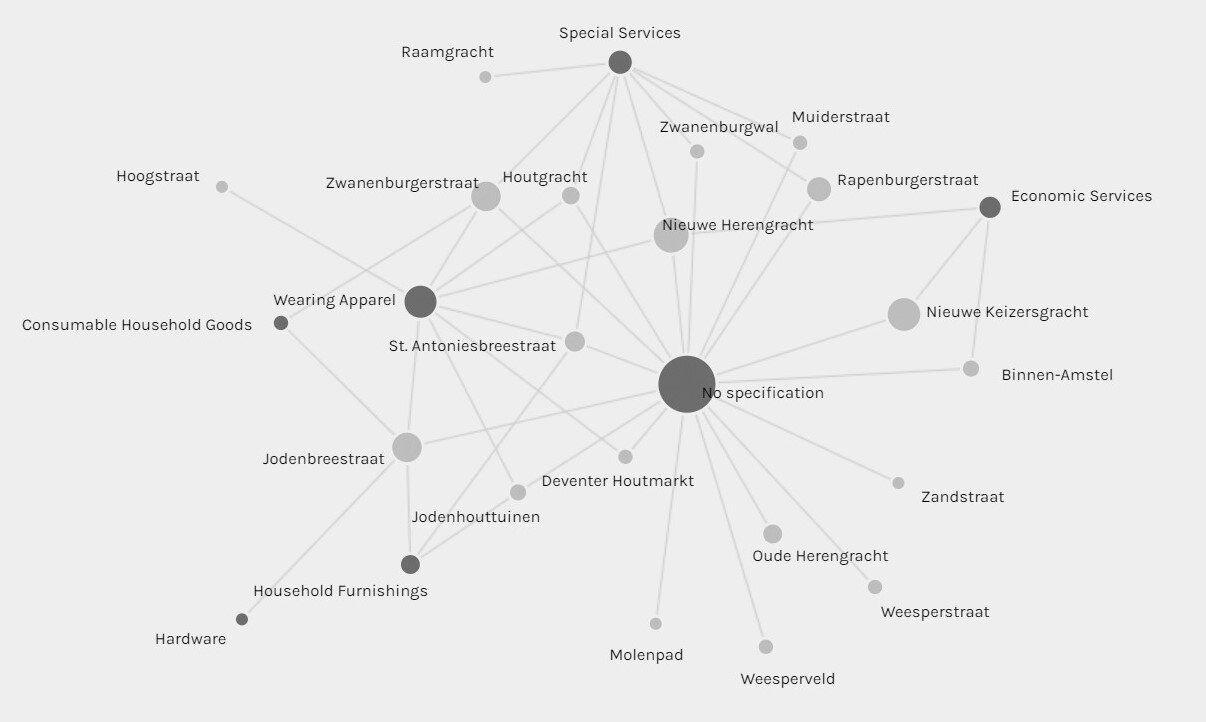

The map shown above shows the addresses of the merchants that appeared in the 1796 register as well as the 1800 one (fig.6). Overall, there were no significant changes between 1796 and 1800 for the merchants who appeared in both registers. It is also possible that the changes were not processed yet. The most striking difference, compared to 1796, was the fact that only one merchant moved, from the Zwanenburgerstraat to the Raamgracht (fig.7). Next to that, only one entry changed in regard to the products that merchants traded in (fig.9). In addition, around 35% of the Jewish merchants that appeared in the 1796 register, did not appear in the 1800 one (fig.8). The streets which lost most merchants were some of the streets that housed most merchants in 1796: the Nieuwe Herengracht (8), the Nieuwe Keizersgracht (7) and the Zwanenburgerstraat (7). The only streets that did not lose merchants were the Zwanenburgwal, the Hoogstraat and the Jodenhouttuinen. However, they did not contain a lot of merchants before. Based on this research, it is impossible to say whether the merchants that disappeared from the register between 1796 and 1800 retired, died, moved, decided not to be included in the register or switched professions. However, it is striking that most of these merchants were housed on the more well-off streets.

Figure 7: Map which shows the Jewish merchant that moved from the Zwanenburgerstraat (below) to the Raamgracht (above) between 1796 and 1800, projected onto Buurtatlas Loman from 1876.

Figure 8: Map which shows the Jewish merchants that appeared in the 1796 register, but not in the 1800 one, projected onto Buurtatlas Loman from 1876.

This means that – assuming the name registers were up to date – the spatial distribution of the Jewish merchant community and the products they traded in underwent little to no change between 1796 and 1800. Although the reason for this is unclear, there are a few factors that could have played a role. There were probably a lot of merchants who did not want to change their profession or the place they lived and/or worked. After all, they had gathered a lot of expertise in the products they traded in over the years. What could have played a role in terms of living situation/place of work is the fact that the Jodenbuurt housed a lot of facilities and institutions for Jewish people, including kosher shops and synagogues. This could prevent them from settling elsewhere. For others, what could have played a part is a lack of education and money to change occupation or living situation on short term. What also needs to be considered is the poor economic situation in the Netherlands at the beginning of the nineteenth century.[5]

Figure 9: Graph which shows where merchants traded in and where they lived, 1796.

By comparing the two registers, it became clear that there did not change a lot for the Jewish merchants that appeared in both registers in terms of trade and living situation. Further research has to be done in order to determine whether this means that there changed little in terms of living situation and profession for Jewish merchants after 1796 on short term. Next to that, this research showed a lot about where Jewish merchants lived at the end of the eighteenth century and what they traded in. In past research, the name registers have only been used to gather fragments of historical information. This research has shown what could be achieved when the registers are used in whole and are approached by using a digital method. Future research could focus on all registers together to see if there are patterns or changes in the places where (Jewish) merchants lived, what they traded in, if there were clusters, study mobility and see if gender played a role in the registers (fig.10 & 11). This way, the registers can contribute to a broader knowledge of the life of merchants in Amsterdam.

Figure 10: Map which shows on what streets female Jewish merchants (widows) lived, 1796, projected onto Buurtatlas Loman from 1876.

Figure 11: Map which shows on what streets male Jewish merchants lived, 1796, projected onto Buurtatlas Loman from 1876.

[1] H.I. Bloom, The Economic Activities of the Jews of Amsterdam in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (2nd edition: New York 1969) 71; R.G. Fuks-Mansfeld, ‘Verlichting en emancipatie omstreeks 1750-1814’ in: J.C.H. Blom, R.G. Fuks-Mansfeld and I. Schöffer (red.), Geschiedenis van de Joden in Nederland (Amsterdam 1995) 177-203, there 189; J. Stoutenbeek and P. Vigeveno, Joods Amsterdam. Geïllustreerde gids (Amsterdam 2017) 18-19 and 43; B.T. Wallet and I.E. Zwiep, ‘Locals. Jews in the Early Modern Dutch Republic’ in: J. Karp and A. Sutcliffe (red.), The Cambridge History of Judaism, Volume 7: The Early Modern World, 1500-1815 (Cambridge 2018) 894-922, there 902-903.

[2] Stadsarchief Amsterdam, Inventaris van de Collectie Stadsarchief Amsterdam: koopmansboekjes (30398).

[3] Buurtatlas Loman 1876 - Amsterdam Time Machine, https://tiles.amsterdamtimemachine.nl/#16/52.3691/4.8935.

[4] C. Lesger, M.H.D. van Leeuwen and B. Vissers, ‘Residentiële segregatie in vroeg-moderne steden. Amsterdam in de eerste helft van de negentiende eeuw’, Tijdschrift voor sociale en economische geschiedenis 10:2 (2013) 102-132, there 109, 112 and 116.

[5] P. Tammes, ‘’Hack, Pack, Sack’. Occupational Structure, Status, and Mobility of Jews in Amsterdam, 1851-1941’, Journal of Interdisciplinary History XLIII:I (2020) 1-26, there 2-3.

I want to thank Leon van Wissen from CREATE for helping me to gather the data from the name registers and dr. Gamze Saygi for the guidance and advice during the research.